Dr Giulia D’Anna explains the correct and safe way to prescribe and perform off-label treatments.

Dermal fillers, and in particular botulinum toxin, are some of the most common pharmaceuticals prescribed for off-label use. Yet many practitioners remain in the dark about recommended guidelines for use and the inner workings of off-label prescriptions. Though botulinum toxin is frequently used to treat the masseter and temporalis muscle, its use is considered ‘off-label’ as it is not officially registered for this purpose with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

Clinicians who use Dysport to treat horizontal forehead lines may be surprised to learn its application for this purpose is also considered to be off-label. With so many go-to pharmaceuticals being used outside of their TGA-defined purpose, it pays to know what off-label prescribing actually entails. Crucially, practitioners must familiarise themselves with the clinical requirements needed to keep patients safe and informed of best practice.

What is off-label prescribing?

’Off-label’ prescriptions refer to medicine that is used in ways other than what is specified by the TGA in its product information document on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). When a drug is prescribed for another indication, at a different dose, via an alternate route of administration or for a patient of an age or gender outside the registered use, it is considered to be off-label.

Since the Therapeutic Goods Act technically does not regulate clinicians, how a device or medication is to be used in an “off- label” way is a decision that every practitioner must make. Despite this, it is common for practitioners to run into trouble due to their lack of clarity on how to properly administer off-label medicine. The off-label use of hyaluronidase to dissolve fillers, for example, has been the subject of an AHPRA investigation as the regulator seeks to tighten oversight of off-label usage.

Why pharmaceutical companies don’t obtain more listings

The high rate of off-label use of pharmaceuticals amongst practitioners can partially be attributed to the lack of incentives for pharmaceutical companies to seek approval for additional indications, especially if there is unlikely to be any additional revenue for the company.

Due to the significant time and cost of undertaking additional research and obtaining regulatory approvals to have each new use listed on the ARTG register, companies are reluctant to sink millions of dollars to expand the listings for a single drug. Once a pharmaceutical is available on the TGA register, companies prefer to rely on practitioners to make sensible use of the drugs, and undertake the appropriate procedures to acquire patient consent.

Off-label use guidelines

Patient consent must always be established every time a drug is used in an off-label application. Every time a clinician decides to use a drug or device for off-label treatment, they must ensure they have informed consent from the patient.

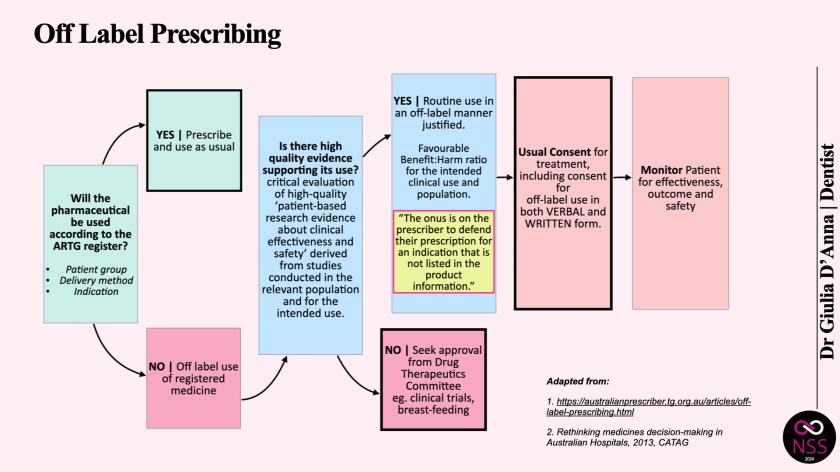

This should only ever be done after extensively weighing up the patient’s risk-benefit profile which takes into account the risks and benefits to the patient, and the evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of the proposed treatment. In determining the appropriateness of using a drug off-label, there should be sufficient evidence to support its efficacious and safe use, and an overall favourable harm:benefit ratio for the intended clinical use and population. Practitioners should proceed with treatments when they have decided that they are strictly beneficial to the patient and there is a good body of evidence for the intended off-label use.

Several guides published by the Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory Groups state that in the event of harm to the patient, “if the off-label use of the medicine in a particular situation is accepted by the practitioner’s peers as constituting competent professional practice, and the patient has given informed consent for its use, then prescribing off-label should not imply negligence.” This implies that there must be a significant body of evidence demonstrating the use of a drug in an off-label way has been tested over a period of time, and there is general consensus among the practitioner’s peers that such use is considered routine.

Off-label use is very common with botulinum toxin drugs, and ample studies of the use of botulinum toxin for the treatment of masseter hypertrophy and bruxism support this. However the evidence of scientific studies do not preclude the practitioner from their responsibility to inform the patient of the off-label use of this drug.

Some practitioners may not be aware that the use of a cannula with dermal filler is also considered off-label, as the delivery method for the drug is different to the ARTG listing. While this is considered the safest delivery method, and is the medical standard in cosmetic injecting, it is again the practitioner’s responsibility to gain consent from their patient for the drug itself as well as the administration of an off-label delivery method.

Is off-label use legal?

In short, the answer is ‘yes”, with the caveat that there must be a large body of evidence that states that the benefit outweighs the risk to the patient, and such treatment is generally accepted amongst your peers. The onus is on the practitioner to consider whether it is appropriate to use the pharmaceutical in an off-label way.

Using a needle with dermal filler, for example, is associated with a risk of around 1:6,410 per vascular incident according to global experts in cosmetic injecting. If clinicians deliver dermal filler via a cannula, the risk becomes 1:40,187, which in light of a number of high-quality and patient-based studies, translates to a safety profile that is very beneficial for the patient.

To help practitioners with their off-label decision making, a number of professional organisations including the Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory group have issued guidelines in relation to off-label medicine use. It is accepted practice that practitioners inform patients and document consent when prescribing off-label. This includes an open discussion about known and unknown benefits and risks. It is crucial that the prescriber documents the reason for off-label use in the patient’s record and ensures that patients are aware of the treatment procedure, along with any reviews that may be required.

Off-label best practice

Every practitioner needs to ensure that patients understand that they are using pharmaceuticals outside of its TGA-sanctioned purpose. Should an adverse event occur following off-label use, clinicians will be relying on informed patient consent they obtained before the procedure. Without it, any potential legal issues would be difficult to defend.

Practitioners who routinely engage in the off-label use of pharmaceuticals are encouraged to examine their consenting process, as well as consent forms, to ensure they are fit for purpose. Even for common drugs like botulinum toxin and dermal fillers, there needs to be clear procedures in place to protect patients and practitioners in the warranted and ethical administration of off-label drugs. If in doubt, it’s recommended that clinicians always err on the side of caution to save themselves from potential minefields further down the line.

This article originally appeared in SPA+CLINIC magazine #98

Read our latest issue below:

There are 5 ways you can catch up with SPA+CLINIC

- Our quarterly print magazine, delivered to your door. Subscribe here.

- Our website, which is updated daily with its own completely unique content and breaking news.

- Our weekly newsletter – free to your inbox! Subscribe here.

- Our digital magazine – click here to view previous issues.

- Our social media – see daily updates on our Instagram, Facebook & Linkedin